The consequences of living in a false reality

One of life’s ironies is that the more you learn, the more you realize how much there is you don’t know. As our knowledge expands, so does our awareness of the vastness and complexity of creation. In a very real sense, knowledge begets awareness of our own ignorance.

In his Republic, Plato offered an extended metaphor that demonstrates the paralyzing consequences of ignorance and the transformative value of knowledge.

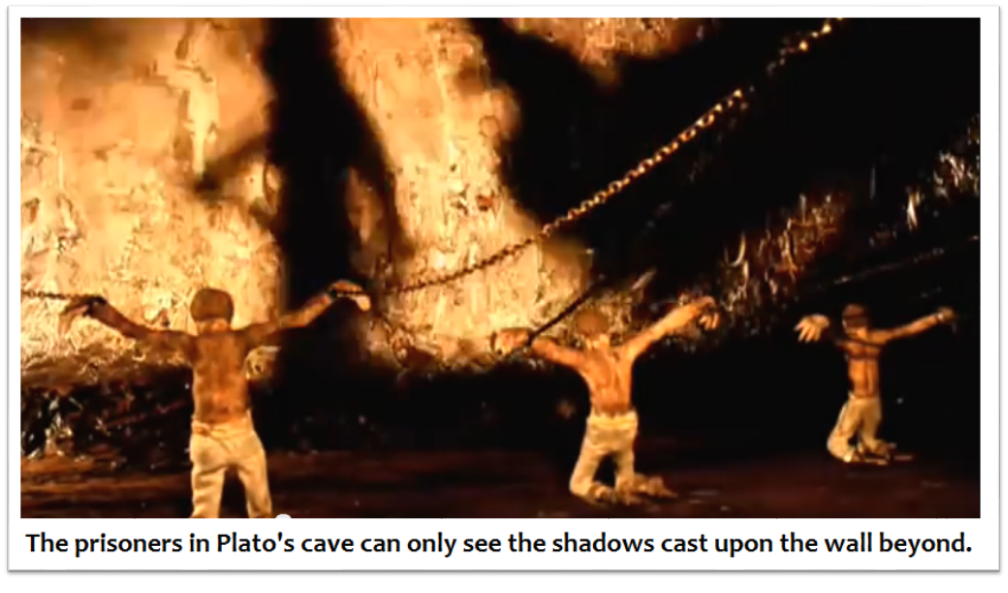

Imagine a cave with three levels. On the bottom level, prisoners are chained facing the back wall of the cave. Behind them on the middle level burns a large fire. Between the fire and the prisoners, puppeteers stand behind a wall and put on a puppet show.

By the firelight, the shadows of the puppets dance and move across the cave wall, creating images for the prisoners to see. The voices of the puppeteers echo off the cave wall. These shadows and echoes are all the prisoners have ever known of life. To them, this is reality, and they concoct myths to explain what they see and hear.

Then imagine one prisoner escapes and ascends to the top level, exiting the cave and entering the real world. What would happen to him?

As his eyes adjusted to the light, he would see birds, deer, bears, and trees of all kinds. He would see flowing water and fish. He would look up and see the sky, the moon, and the stars. He would hear the lion roar and the wind blow. He would experience sunlight for the first time, and he would be overwhelmed by the magnificence of the real world.

But what would happen if, in his excitement, he returned to the cave? His vision would suffer in the dim light, and he would no longer be entertained by mere shadows on the wall.

Would the other prisoners believe the stories he told of birds and trees and bright sunlight outside the cave? No. They would find his tales ridiculous, even dangerous, a threat to their narrow vision of reality. To them, life would still consist of only shadows and echoes. They would never believe unless they too were freed from the shadows and led outside into the light.

Plato’s parable—the source of our notion of “enlightenment”—has been studied for two thousand years because it reveals so much about our human condition.

Like the prisoners in the cave, we are born into ignorance. As children, little of our knowledge is gained independently. We rely on our parents, teachers, and other authority figures to explain the world around us.

If we’re lucky, our “puppeteers” provide us with information that, while limited, provides a foundation for growth and a curiosity for learning. As we mature, they encourage us to venture out of the cave and climb up toward enlightenment, where we experience the world anew, seek out knowledge, and reap a fuller, more abundant reality.

Yet some are not as fortunate. Without benevolent players to guide us, the puppeteers who influence us are just as likely to distort our visions and hinder enlightenment. Consider the consequences of abusive parents or political rulers who suppress or manipulate citizens with false promises or deceitful information.

As an illustration of living in ignorance and oppression, Plato’s cave allegory has been a mainstay of philosophical thought for centuries. Yet the allegory has never been confined to the dry discussions among academics.

In fact, the images and themes of the cave have recurred in Western art and culture for centuries. In Paradise Lost, Milton referenced Plato when he wrote, “Long is the way and hard that out of Hell leads up to light.”

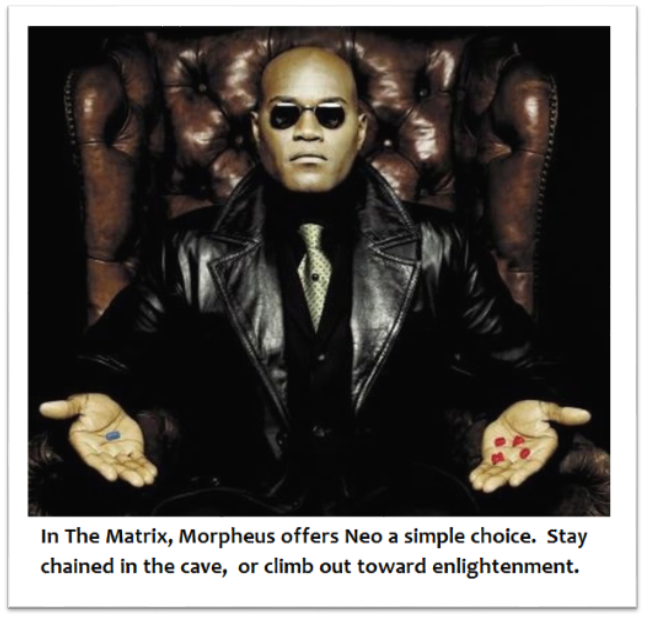

Even modern movies borrow from the ancient allegory. Released in 1999, The Matrix was not only an innovative action film but also a condemnation of living falsely in a contrived world oblivious to reality. Take the blue pill and continue existing in ignorant bliss. Or take the red pill and climb out of the cave into the real world, full of dazzling beauty and crushing cruelty.

And the 2015 film Room explores the plight of a mother and son imprisoned for years in a small shed, and the false reality she creates to explain to him their tiny world—until the dramatic moment when they finally flee cave.

These instructive films demonstrate that whether the darkness of the cave stems from ignorance, poverty, or oppression, the consequences are as debilitating to society as to the individuals who comprise it. Our duty is, as ever, to rise above, because our true home is outside the cave, in the world and the light.

But just as important as our climb out is our duty to return to the cave and foster the climb of others. For society to progress, we each must periodically return to the cave to assist others on their ascent—our children, students, and the underprivileged in our communities. Giving back, lending a helping hand, mentoring, and guiding others is a fundamental, co-equal component of the social contract. Because the cave is real, and the world outside exists whether we believe in it or not.